Manufacturing miss exposed in Aussie inflation print

Image: Pixabay

Last week, the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) released its February Statement on Monetary Policy, or SMP for short.

The SMP showed that ~80% of the items in the Australian CPI basket are still inflating. No great surprise there.

But today I wanted to look at prices in the Australian ‘goods’ sector and compare their trajectory to what we’re seeing in the U.S.

As a refresher, prices for goods have started to dis-inflate in the U.S. for the first time, and this was one of the key reasons for the Federal Reserve’s small 25bp rate hike.

“CHAIR POWELL. So, I guess I would say it this way. We can now say, I think, for the first time that the disinflationary process has started. We can see that. And we see it really in goods prices so far. Goods prices is a big sector.” February 1, 2023

And notably, last night’s CPI print released by the U.S. Bureau of Labour Statistics confirmed that prices for new and used motor vehicles and trucks continued to dis-inflate in January (as did fruit and vegetables) as supply chains repaired - although overall CPI increased slightly to 6.4% over the last 12 months.

As usual, it’s the rate of change that matters, and it’s been slowing markedly in the U.S.

However, unlike the U.S., consumer-durable goods prices in Australia are still accelerating 👇👇👇

Source: RBA, SMP, Feb 2023.

The RBA’s SMP blames these higher prices on higher upstream costs, such as freight and commodity prices.

This is correct and easy to see given the distances between Australia and our import partners in the U.S., Canada, Denmark, Thailand, China and even our neighbours in New Zealand, etc.

However, the inflationary effects of the above, particularly for manufactured goods are amplified by two stubborn tectonic-like factors:

There is almost no manufacturing base to speak of in Australia due to prohibitive labour rates and the lack of fiscal investment foresight that has created a comparative disadvantage. In turn, this continues to expose Australians to the ongoing exportation of raw materials and their re-importation in the form of value-added foreign intermediate and finished goods that are subject to volatile freight rates and protectionist taxes and imposts that in some cases seek to protect industries which no longer exist in Australia.

A weaker dollar against the world’s reserve currency, which when the USD strengthens and/or interest rates rise (like in the December quarter), amplifies our exposure to imported inflation 👇👇👇

Geographical distances/isolation, the lack of downstream manufacturing/processing, and having a lower yielding currency than the USD are some of the reasons why the path to disinflation in goods prices is probably going to take longer to happen here, than in the U.S.

This of course is unless for some reason goods inflation picks up again in the U.S., or if we start to consume at a lower rate as a result of declining household after tax disposable income, and/or if Governor Lowe gets serious about interest rate hikes while he is increasingly under fire for his monetary policy soup.

I know that we can’t just pick the country up and move it around the globe (unless Elon Musk can show us how) and I also understand that we are still operating within the USD reserve currency construct.

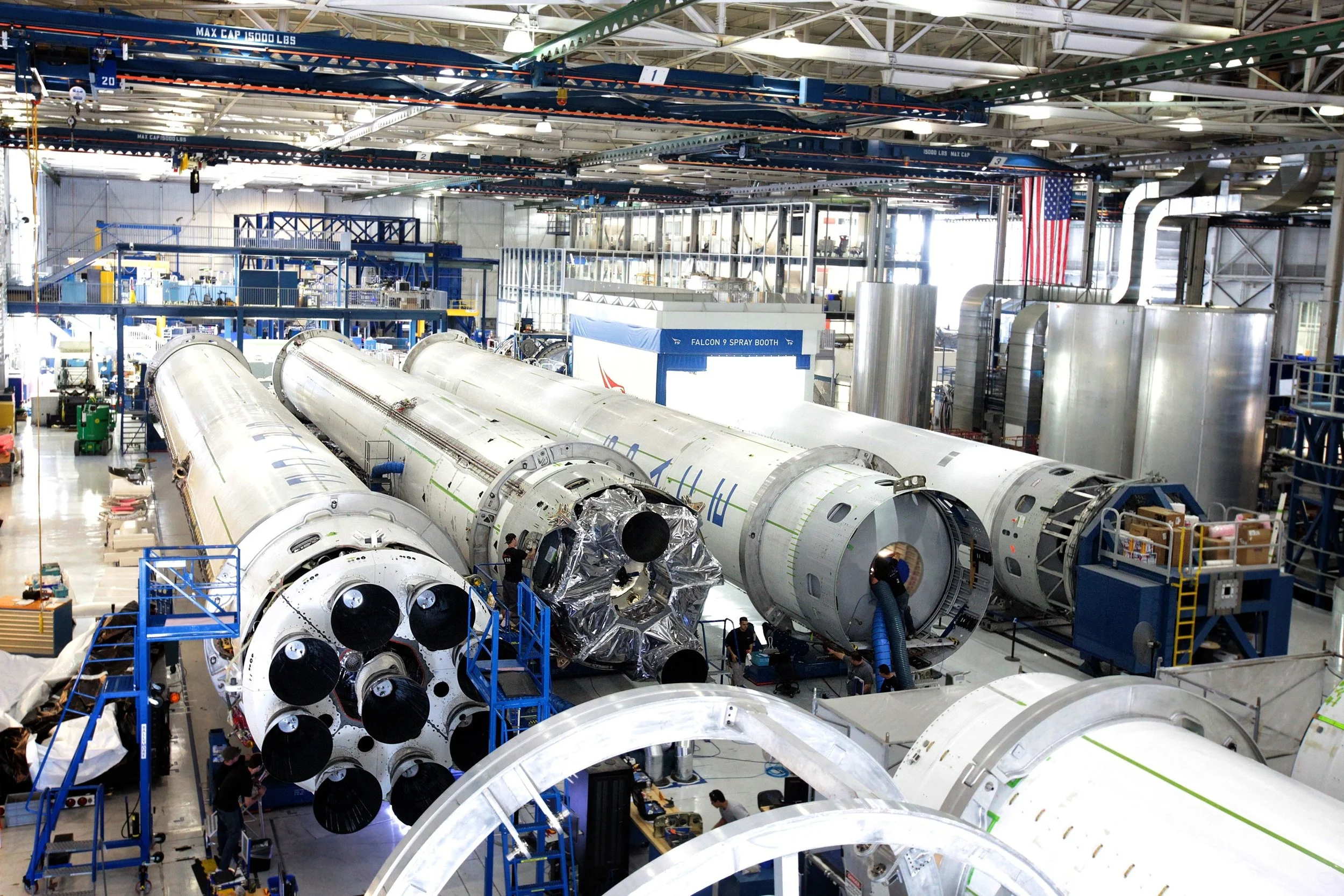

However, we can try to reduce our access/import price related issues in the future (for the next war, pandemic or de-globalisation event) by onshoring/re-shoring certain manufacturing and processing industries.

In Australia, this was a bit of a tall order in the past given labour intensity, but perhaps not so now. That is to say that life has moved on as it always does due to technological advancements.

Adding to that has been the U.S./Sino trade war, COVID and Ukraine which have created the impetus for even more change.

Sure, regulation in some areas is still required as is (sadly) political will, but an increasing avalanche of technology exists to spawn a viable and politically acceptable re-shoring/on shoring, without having to dictate a lower standard of living for sections of the community.

The answer is suitably balanced and incentivised public/private tech-enabled Industry 4.0 investment, at serious scale.

And at the risk of sounding like a broken record, I am again proposing that it’s time for government to fix the fiscal.

It doesn’t matter if it’s federal or state based - but we need it to be sustainable with sufficient longevity/enshrined incentives and parameters to satisfy counterparties and financiers.

So, in summary, let’s rethink what we do with our commodities and natural resources and build new industries for the benefit of all.

We can start by developing programs to encourage public/private investment in robotics, Industry4.0 manufacturing and downstream processing/value-adding as well as way cheaper energy sources and educational/upskill/reskill programs to develop and run it all.

And in the meantime, let’s not assume that Australian CPI will follow what we’re seeing in the U.S., or anywhere else for that matter, because our tectonics move in different ways.

See you in the market.

Mike

Image: Tom Fisk

Next Level Corporate Advisory is a leading M&A, capital and corporate development advisor with a multi-decade track record in transforming businesses and helping owners with customised financings, mergers, acquisitions, divestments and investoments in and out of Australia.

All text (other than for quotes and image text) is copyright NextLevelCorporate.