Has Bernanke/Powell’s fear of 1929 put us on the same track? Part 4 of 5

Alexander Zvir

Part 4 of 5.

This post is the fourth of a five part series where we look at the actions of the 1929 and 2020 Federal Reserve Boards in an attempt to find out whether the low cost money punchbowl is again likely to be left out for too long, like it was in 1929.

If you missed Part 1, tap here. If you missed Part 2, tap here. If you missed Part 3, tap here.

In this fourth instalment, it’s time to get to the heart of modern central banking in the U.S.

So today, I’m going to talk about the architect of QE Infinity - ex-Fed Chair, Ben Bernanke.

Ben Bernanke, the architect of modern QE Infinity.

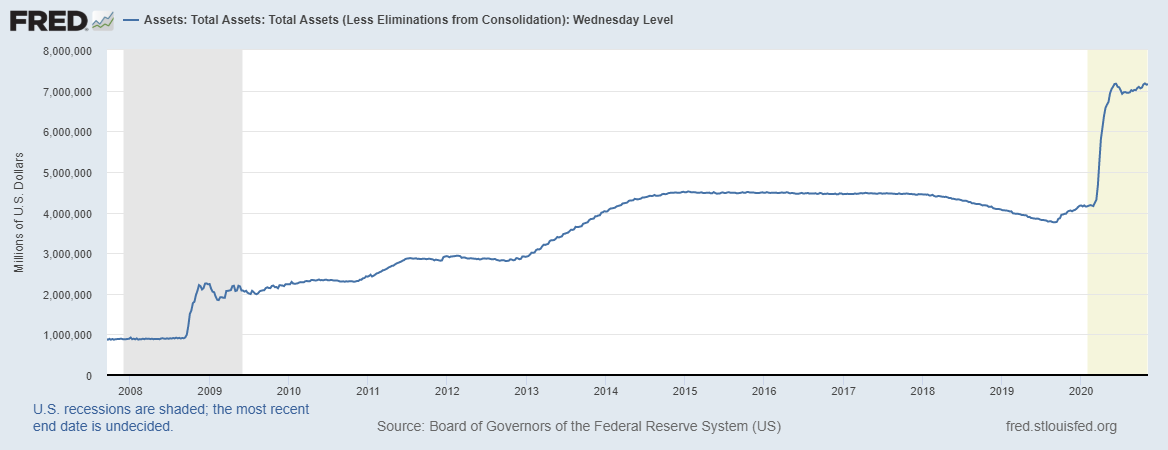

In 2008/2009 and in response to the sub-prime crisis and collapse of Lehman, Fed Chair Ben Bernanke teamed up with Tim Geithner and Hank Paulson to kickstart what has now become QE Infinity. This included emergency bond purchasing in 2008 and a 22 bank bail-out in 2009.

At the time, Bernanke said he would return what be came a $2.2 trillion balance sheet to a more normal level of around $900 billion, once the crisis was over.

He did not do this. The Fed’s balance sheet now sits at $7.1 trillion and interest rates are at zero.

And by 2015, Janet Yellen (who replaced Ben Bernanke as Fed Chair) finally decided the punch bowl had been left out for too long. That decision was made relatively early in the asset inflation cycle - and way before the 1929 Fed made its call back in the day, as we’ve seen in previous instalments.

Chair Yellen, implemented the first of the five rate hikes that she was to preside over before being replaced by Donald Trump. She also started the balance sheet run-off. That is, decreasing the Fed’s reinvestment in maturing bonds.

But the looming ‘stake in the heart’ for the equities market was too much for Donald Trump to imagine/tolerate, so he replaced Janet Yellen with his own appointee, current Fed Chair, Jerome Powell.

A new Fed Chair, who started out in Janet Yellen’s footprints, but then turned dovish, and then a new bull run.

Add in some Trump tax cuts and further rate decreases by the Fed (along with a resumption by the Fed of massive bond purchases), and the U.S. has experienced the longest and most irrationally exuberant bull market in U.S. stock market history - and also in bonds with interest rates falling and prices rallying.

Such is the effect of low/zero interest rates.

Massive secondary market asset inflation, with investors pushed further out along the risk curve. No price inflation to speak of.

COVID-19 has shown us that it’s a slippery slope without end, if fiscal spending, growth and productivity are not present. At this time, the lights in major parts of the economy are being left on as a result of welfare fiscal, not fiscal spending for growth.

But going back to Chair Bernanke, why did he leave the punch bowl out for that long?

One of the reasons can be seen in his apology, six years prior to the GFC, and rightly or wrongly, his perception of the ghosts of 1929 which appear to have shaped his ‘liquidity is the only thing that matters during a crisis’ ideology.

Rewind to 2002, and the Bernanke clue.

Ben Bernanke provided an uncomplicated insight into his position on liquidity and QE, when he spoke on the occasion of Milton Friedman’s ninetieth birthday, in 2002.

After praising Friedman and Friedman’s co-author Anna Schwartz on their work ‘A monetary history of the United States’, he pointed out four reasons why the lack of monetary intervention (i.e., managing down interest rates) was the primary cause for the Great Depression.

While this is still arguable, his view was that flooding the economy with liquidity is the only way to avoid a recession/depression.

And it was the conclusion to his speech that provides the biggest clue to his actions in 2008, and Jerome Powell’s actions of today.

He apologised for the Great Depression by saying:

“……For practical central bankers, among which I now count myself, Friedman and Schwartz's analysis leaves many lessons. What I take from their work is the idea that monetary forces, particularly if unleashed in a destabilizing direction, can be extremely powerful. The best thing that central bankers can do for the world is to avoid such crises by providing the economy with, in Milton Friedman's words, a "stable monetary background"--for example as reflected in low and stable inflation.

Let me end my talk by abusing slightly my status as an official representative of the Federal Reserve. I would like to say to Milton and Anna: Regarding the Great Depression. You're right, we did it. We're very sorry. But thanks to you, we won't do it again.

Best wishes for your next ninety years.”

So, there it is. Bernanke’s interpretation, conclusion and personal view – the idea that free and easy monetary policy should be made plentiful so as to not destabilise the economy, and therefore his view that the May 1929 rate hike was probably the final cause of the 28 October 1929 stock market crash, and the Great Depression. He promised not to repeat it.

But what if Ben Bernanke was wrong?

What if the economy had already been destabilised by low interest rates and the lure of high and ever increasing asset prices because rates were kept too low too long - and that meant that the central banking system was either unable or unwilling to ween the market off low rates, years earlier.

After all, when the c-suite can make more money from the effects of cheap debt and buy-backs, than actually growing a business, certain decisions are made at the expense of others. It’s those expensive decisions that can contribute to corporations taking their eyes off the ball and letting competitors in, domestic and foreign. The latter being clearly seen today as one of the key precursors of the unresolved U.S./Sino trade war.

That said, Ben Bernanke’s contrary view has probably made modern monetary theory more popular today, with the belief that one only needs to unleash a bond buying bazooka to manipulate down interest rates in order to provide rivers of liquidity to stimulate credit, investment, and growth. We shall see.

And, in March of this year, he was followed, and frankly outdone when current Fed Chair Jerome Powell hijacked the death star and squirted out trillions of bond purchasing, in an almost immediate response to the COVID-19 shock.

Within 6 months (as opposed to nearly three years in the 1929 timeframe) the stock market had retraced and exceeded its COVID-19 low, as of October 2020.

But again, that does not mean that central bankers are correct in going down this track again - because like a COVID-19 virus, there could be serious side effects in a world where there is no real growth and welfare fiscal (when it comes again) is paying for past spending, not new growth.

Rather, and looking back at the years just following the GFC, it could simply mean that the Bernanke and Powell Feds have left the zero cost money punch bowl out for too long, forcing the Fed (and other centrals that need to keep up to avoid their own currency problems) down a slippery slope to zero/potentially negative interest rates, which is where we look to be headed.

Economic destabilisation - monetary stimulus without fiscal stimulus through a Keynesian lens.

As the reserve currency, manipulating interest rates and expanding the money supply is the ‘easy’ way to go about managing the economy.

Plus, we now have secondary market asset prices which are difficult to reconcile to primary market fundamentals, along with increasing social inequality as a result of the uneven wealth effect that comes with high asset inflation and low price inflation.

I try to always provide a non-biased view on everything I write about. But I will make an exception just this once.

And that is to say that Janet Yellen was correct in her attempts to slowly but surely guide the market back to a more commercial level of intertest rates in the form of rate hikes and the balance sheet run-off in 2015.

At that time, the pump had already been over-primed for too long and was overflowing - for no increase in productivity. Yellen was right.

But, interference from the White House put a stop to the normalisation, at a time when it could have made a massive difference.

In simple terms, Chair Yellen’s time in office was a missed opportunity to normalise the cost of/return on money (i.e., interest rates) and the Fed’s balance sheet, and stabilise the economy ready for the next crisis.

On top of that, by 2015 there had been very little economic growth primed by fiscal policies since the GFC, with governments preferring to see central banks weigh in with monetary policy.

But Keynes said the stabilising effects from monetary policy need to come from monetary policy and fiscal policy working together.

That was not present is 1928, nor is it present now and that is what central bankers are missing. They’re calling for it, but not getting it.

And with all the heavy lifting left to the Fed, interest rates will likely go to zero and potentially below.

If we do go to negative rates, there is a good case to say that banks should be done away with, because negative rates mean banks no longer act as effective money transmission mechanisms.

Today, we live with the stubborn spill-over from a broken fiscal where in response to the GFC and COVID-19, successive Fed Chairs have acted to inject liquidity and lower the cost of borrowing (and servicing an even bigger debt stack) in order to stimulate investment, growth and employment in pursuit of maximum employment. But, without the fiscal growth spending sidecar. Fiscal is just too hard, it seems.

Maybe Joe Biden can fix the fiscal once inaugurated. He’s got the Presidency and the House, but taking control of the Senate away from Republican majority leader Mitch McConnell would certainly help. At this stage, we don’t know what will happen on that and other political fronts so we will have to wait until the Georgia run-off elections in January 2021.

In the next and final instalment: We conclude on the question of whether the monetary punchbowl has again been left out for too long, like it was in 1929.

Mike.